Natural areas in the West are going fast. With each flight home, we get a bird’s eye view of sprawling new roads, oil wells, and pipelines. The Oregon woods we explored as kids are now stumps without songbirds. We see fewer stars through Santa Fe’s brightening lights.

Yet, from governors’ mansions to the halls of Congress, questions about land and wildlife conservation command relatively little attention today. The conventional wisdom seems to hold that the most consequential battles over America’s wild places are already settled. President Theodore Roosevelt, Sierra Club founder John Muir, and the environmental activists of the 1960s won protections for national parks, national forests, and wilderness areas. In the eyes of some politicians, the West’s open spaces are not only well protected, but too well protected. An anti-parks caucus in the U.S. Congress, for example, wants to block new national parks and sell off the West’s national forests to private owners.

As members of the Public Lands team at the Center for American Progress—and as people who love and advocate for the outdoors—we believe the disappearance of open space and wildlife habitat in the West is indeed a problem. But until this project, we weren’t able to adequately describe or quantify the scale of this problem. We wanted to know:

How fast is the United States losing natural areas in the West and—importantly—why?

This project seeks to answer these questions, with the help of some of the country’s top researchers in landscape ecology and conservation biology.

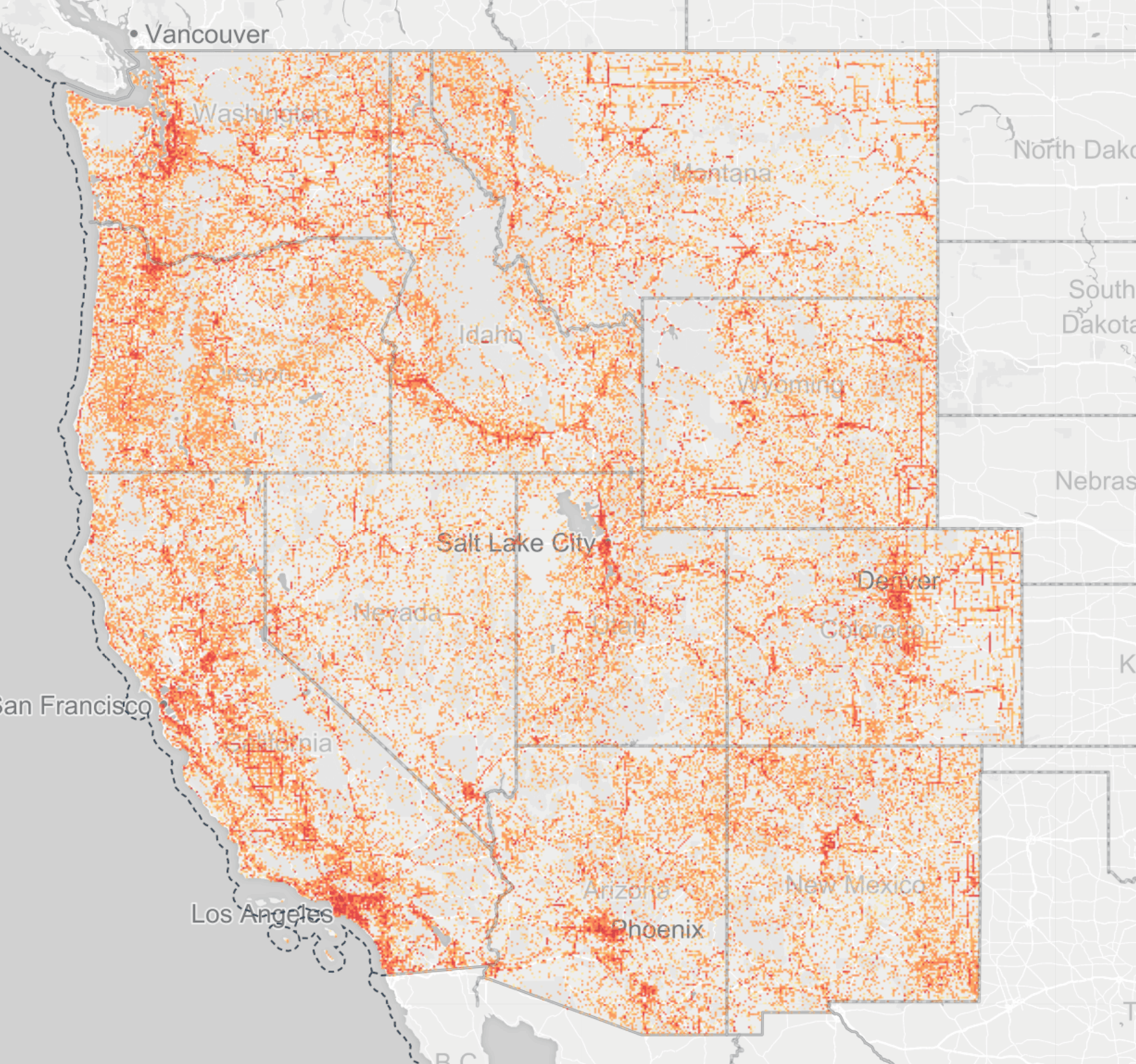

A team of scientists at the nonprofit Conservation Science Partners, or CSP, analyzed nearly three dozen datasets; a dozen types of human activities; and more than a decade of satellite imagery for 11 western states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Here is what they found: Human development in the West now covers more than 165,000 square miles of land. That is roughly the size of 6 million superstore parking lots.

This development is growing fast. Between 2001 and 2011, natural areas in the West—including forests, wetlands, deserts, and grasslands—were disappearing at the rate of one football field every 2.5 minutes.